My favourite thing about Far Cry 2 is that there isn’t a twist. Its emotional impact doesn’t come from making you think you’re the hero and then somehow making your actions have horrible consequences, or making it turn out you’ve somehow been deceived or controlled. Nor are you somehow responsible for everything that happens, reducing the story to one of individual guilt. It just stays true to its premise: you’re a mercenary in a small African country ravaged by civil war. So by definition, the things you do are extremely unlikely to help.

When the game starts, you’re completely in over your head. You were supposed to track down and assassinate the Jackal, an arms dealer, but instead you’ve contracted malaria, your mission is a failure, and you’re caught between the two sides of the civil war. It’s a very immersive introduction, helped by the excellent environment design. The distinct architectural styles, the thick jungle, the badly-maintained roads – all of it feels like a real place. If you’ve ever been to a very poor country (even without a civil war currently happening), there’s a lot you’ll recognize. A huge amount of work has clearly been put into making the game’s setting as believable as possible.

Far Cry 2‘s game design is controversial. Many players felt frustrated by the constantly respawning guard posts, the cars patrolling the roads, the extremely limited ability to fast-travel between locations, and the weapon degradation. In the almost fifty hours I played, I also found myself occasionally irritated by these things, particularly when I had to repeatedly traverse the same terrain and thus clear out the same guard posts over and over. On occasion, I resorted to only playing the game in short bursts. And yet I think these choices were valid, even if aspects of them could have been executed better.

By forcing you to stick to its reality, to its harsh rules, the game starts having an effect that I have very rarely encountered, the other case being the excellent S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games. As you played those games, you started learning how to survive in the Zone. This felt like acquiring a very specific set of skills, habits, reflexes, combined with increasingly detailed knowledge of the Zone’s geography and the behavioural patterns of its inhabitants. You started feeling like you were that character you were playing, because you knew the Zone as a place, almost as a way of life, not as a level or a series of challenges. The same thing happens in Far Cry 2. You start developing strategies for dealing with certain situations. You figure out the fastest and safest paths to places. You find yourself instinctively alert for the sound of engines, for headlights in the night, for rustling in the undergrowth. You start to become the hardened, paranoid mercenary you’re playing.

Combat in Far Cry 2 is brutal and fast. Enemies are smarter than in most games, trying to outflank you, run you over, searching for you if they lose you, helping injured comrades, and so on. Between that, the possibility of a patrol car suddenly joining the fight, and the game’s stunning simulation of fire, you get some of the most memorable fights I’ve ever encountered in a game. At first, these fights are terrifying and exhilarating, and surviving one makes you feel great. After all, you’re the underdog, and the people you’re fighting aren’t exactly innocent. But after a while, it starts to get ugly.

It’s not just the missions themselves. Sure, most of what you do is awful, but it’s not awful in some manipulative way, where you’re trying to save the orphans but the orphans are secretly explosive clones who will destroy an abortion clinic if you don’t torture them (i.e. the Battlestar Galactica approach). You’re blowing up infrastructure, assassinating targets – the kind of thing a mercenary does. It becomes clearer and clearer that neither side cares about civilian lives, or even about the ideologies they claim to espouse, and your actions are definitely not constructive in any way. Some of the missions are more disturbing than others, like destroying a source of medicine or assassinating a radio propagandist.

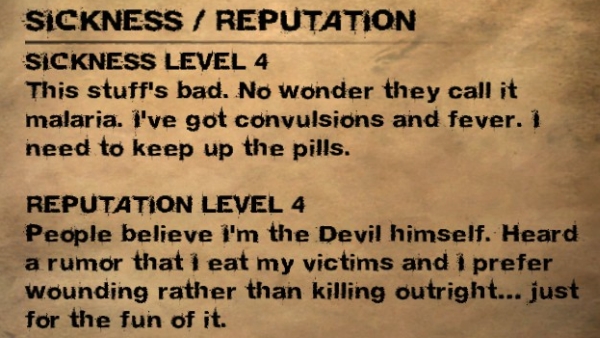

But an equal amount of disturbing violence is simply the result of the gameplay. You’ll shoot people in the back as they’re limping away from you. You’ll wait for someone to pick up an injured comrade to carry him to safety and then kill them both. You might even use that as a strategy, injuring some enemies instead of killing them outright. You’ll casually put bullets in the heads of enemies who can’t walk anymore. (I couldn’t stop thinking of that clip from the Charlie Hebdo murders.) You’ll kill enemies who are so terrified of you that they’re babbling about how they don’t want to die.

None of this is a cutscene. None of this is forced on you. You’ll just do it because you’re trying to survive.

Some have criticized the game for being too long, but I think its length is actually essential to the player’s emotional arc. At some point, you are no longer the underdog. You’ve got the best equipment, you know the terrain, and you’re really good at this. But you’re not a hero. Quite the opposite, as is reflected in your Reputation statistic. Some people think you’re the Devil. And while you’ve never done anything out of cruelty, at some point you start to recognize the unspeakable horror of this neverending slog through hell. You’re killing and killing and killing and what are you accomplishing? Nothing.

There are some minor good things you do, almost accidentally in some cases. To get more malaria medicine, you have to help the Underground, an organization dedicated to helping refugees out of the country. (The EU would see this as your only crime.) There is also an African journalist trying to document the things that are happening and expose them to the world. These ordinary Africans are easily the most human, most heroic characters in the game.

And then there is the Jackal, a character who, in his own words, “used to be you.” Predictably enough, the game is influenced by Heart of Darkness, and the Jackal is its version of Kurtz. But he is quite different from the novel’s ivory trader or the equally-famous colonel from Apocalypse Now. The Jackal isn’t a leader, for one thing, and he isn’t admired or worshipped by the natives. As noted above, the civilian characters of the game, though sadly rarely seen, are the least savage. The Jackal has simply taken the disgust the player is starting to feel to its ultimate extreme. He does want to “exterminate all the brutes” – but in this case, that means both of the sides in the conflict, as well as the mercenaries – including you, and including himself.

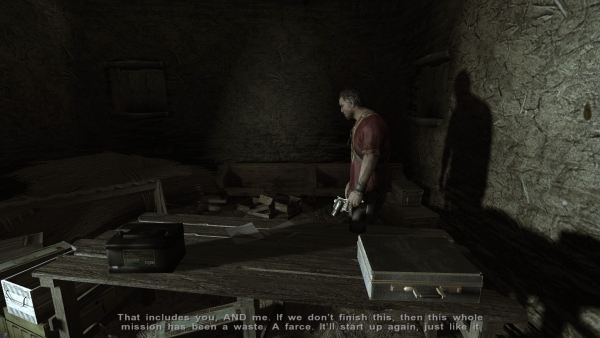

Your encounters with the Jackal near the end of the game are particularly powerful, because you understand where he’s coming from. You’ve slaughtered so many people. You’ve worked for both sides. You’ve seen the horror and you feel dirty and you want it to end. And at no point has the game popped up some self-righteous character to preach at you about your personal responsibility. If anything, the sane people you meet are grateful for what you did for the Underground and your journalist friend. Ironically, the Jackal is the one person who really understands you, who can talk about the cancer that you’re part of without sounding judgemental. He is you.

At the very end, you try to do something good. You destroy the leadership and help the refugees escape. One of you must sacrifice himself, and the Jackal suggests that the survivor should kill himself as soon as the refugees are safe. The cancer must be destroyed. It’s the only logical conclusion of what you both have become.

But does it work?

By not reducing the civil war to a matter of personal guilt (your character experiences personal guilt, but the war is not caused by that), the game avoids the kind of simplistic moralism that games with a postmodern liberal political outlook fall prey to. That’s not to say the game is Marxist, but it certainly presents a situation that has historical, material causes. And as such, the actions of isolated individuals like yourself and the Jackal, while having an impact, can’t really fix the underlying problems.

In the end, all of this is part of a much bigger problem, which too many powerful people aren’t interesting in solving, because they are far more interested in the resources the country has to offer. More soldiers and more weapons won’t help bring peace. Nor will claiming that one side is “moderate” and helping it destroy the other. This isn’t about ideology; it’s about power.

You know that, and that’s the game’s biggest triumph. You know that because you remember the towns, the roads, the jungle, and the endless killing.

You know that because you’ve been there.