In my early university days in Germany, I made the rather painful mistake of picking something called Theatre, Film and Media Studies as one of my majors. I was fully aware that this department only cared about the theoretical/academic side of things and wouldn’t teach us how to make movies or direct plays, but I was under the impression that it would at least be useful in terms of expanding my horizons and giving me interesting material to sink my teeth into.

The reality was more one of mind-numbing boredom as tedious quacks with a hatred of popular culture and an unhealthy obsession with the misanthropic works of Theodor Adorno expounded endlessly on topics that even a small child could both understand and dismiss as precious nonsense. One bit stood out, though: their ideas about subversive art, particularly in the theatre.

As the majority of students tried to keep their eyes open – the rest choosing to sleep under the tables – our distinguished professors explained that for art to be truly subversive and transgressive, it had to break with the conventions of the form. Look, they said as they showed us a recording of naked actors babbling incoherently, with no artistic intent or thematic cohesion, look at how this breaks the conventions! This will truly shock the audience into engaging in a whole new way! The boldness of putting a naked man on stage! The radicalism of retelling the story from a Freudian perspective! The subversiveness of projecting some piece of unrelated video over the actors as they spoke their lines backwards!

A few years later, a friend went to the theatre with his mother. He thought the performance was odd. “Did it involve a naked man and a projection?” I asked. “How the hell did you know that?” he said, genuinely surprised. “They all do,” I sighed.

They all did, and it had been that way for decades. And yet the academics persisted in making grandiose claims about disrupting a status quo that no longer existed, and artists kept producing plays that consisted of nothing but such “radical disruptions” of a dead format. Art, storytelling, vision – all these things had been excised from the process, along with popular audiences who enjoyed the work itself, the latter replaced with elite audiences who cared about being seen enjoying the work.

This wasn’t a failure of imagination, however, although it grew from one. It was a deliberate scam, a hostile takeover by hucksters and con men. Much like the purveyors of “modern art” who are entirely aware that what they do is a business designed to create money without effort, these artists and academics had no belief in what they did. Instead, it was a kind of scammer symbiosis: the academics legitimized the meaningless nonsense cooked up by bored writers and directors (following a pretty much identical “radical” formula), who in turn produced material for the academics to write unreadable, jargon-filled essays about. A system of empty-headed idiots producing nothing and glorifying themselves for it, largely funded by taxpayers.

It’s surprisingly easy to set up systems like that, and they exist all over the arts. What makes them so effective is their two-pronged method of attack: if the artists produced this work on their own, to be judged by audiences, they would never be half as successful. But the legitimacy provided by the academic half of the scam makes questioning the supposedly “radical” works much harder – just say that artists like Duchamp or Beuys or Hirst are scammers and see the immediate outrage this causes, even though plentiful evidence of their true intentions exists. And the more shameless they become in their scamming, the more they just sell you their unused trash (like Duchamp selling his bottle rack as art, perfectly aware that he was just scamming people), the more they don’t even do any of the work themselves, exploiting other artists to mass-produce their simulacrum of art, the more those who have built an entire artistic world on their backs will defend them – if only because there’s money involved.

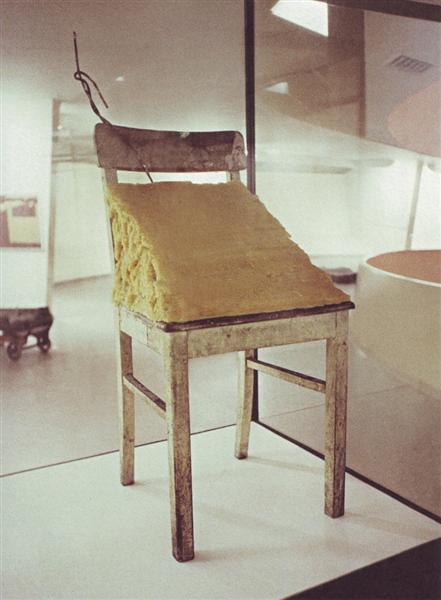

All of this is supported by the most ingeniously shallow yet seemingly deep question ever asked: but what does it tell us about art? With this vague, fundamentally meaningless meta-question, the worst, most obviously ludicrous work can be raised to a status of great artistic significance. Is a toilet seat art? Is a bathtub art? What does this lump of fat tell us about art? No vision, no talent, no transcendence is required – this question allows anything to become art, and thus anything to become product, to become the subject of essays no-one will read and exhibits no-one will enjoy, which will nevertheless generate meaningful amounts of money for the scammers involved.

Perhaps the worst effect of this feedback loop of deception is that, from the outside, the field appears to be healthy. Works are being produced and written about. The “scene” seems lively, if hard to understand for the unwashed masses. But underneath all is rot. It’s not just a lack of new ideas – it’s a lack of anything at all.

If death was apparent, if the field seemed empty, something new might take root. But the shambling corpse – still profitable to some – keeps going, disconnected from the people, disconnected from reality. And where are new artists to turn?

So they get swallowed up by this purposeless machine, the more cynical amongst them richly rewarded for consciously signing up for the scam, but even those who aren’t cynical, who have vision and talent, pushed and pushed towards conformity. The pushing doesn’t even need to be obvious: artists are desperate for validation, and giving them that validation only when they produce works within the accepted framework will guide them towards performing as the system desires. Tell them that they are radicals, that their work is subversive, and they will feel so proud of themselves for fighting the good fight that they’ll keep digging their own graves, thinking that they’re opposing the status quo.

The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled wasn’t convincing the world he didn’t exist, it was rebranding himself as God.

Art does not exist in a vacuum; each of us builds on what came before. But art also does exist in a vacuum, creating something mysteriously unique out of entirely common elements, not only because of its context but in spite of it – much like life. When art is reduced to a reaction, to a relationship to its context, it is stripped of what actually makes it truly powerful – the creative spark, the paradoxical, visionary process that creates meaning and transcends the limitations of the human beings creating it.

When art is sold to you purely on terms of how it relates to its context – groundbreaking, radical, subversive, experimental, brave, etc. – beware of scammers. Great art is great art, no matter which human being creates it, no matter where or when its creation takes place, because the thing that matters about art is that it’s a window to something greater than time and space. Great art does not need to subvert some imaginary status quo; its very existence challenges everything.