I’ve experienced racism as long as I can remember. As a small child in Greece, it was because I spoke German to my mother, so other children would mock me, screaming “Hitler! Hitler!” on the playground. As an adult living in Germany, it’s because I’m Greek, and Greeks are supposedly lazy and corrupt leeches. Racism and xenophobia have always been with me, and it’s not really gotten much better, especially with the economic crisis pushing all ideologies towards their extremes.

Now, with Brexit and Trump, I’ve seen a lot of people get very angry at the perceived “white working class” responsible for these things. That a lot of it actually comes from middle-class voters – and that non-white and non-male people also voted for these things – is a different issue; let’s stick with the racist underclasses for now.

I happen to know a lot of German working-class racists. I know even more who are so poor that they don’t qualify as working class, but as lumpenproletariat. I’ve heard them discuss their ideas, sometimes with me present. They think Greeks are crafty, greedy foreigners just looking to exploit honest, hard-working Germans. They think Greeks are lazy, living in luxury. They think Greeks work few hours, retire early, and get huge pensions. They think Greeks literally owe them money, which they are very angry about, because they are genuinely poor and struggling. They think Greeks should be punished for their crimes against Germany. The only thing they hate more than Greeks is those refugees, who are actually lying economic migrants, coming here to steal their jobs and rape their daughters.

“So, what, you want us to like these people? This is the working class you want to build socialism with?”

To answer your questions: 1) no 2) yes.

I mention my personal experiences – due to a sarcastic article I once wrote, this site still gets hits from people searching for “kill all Greeks” and meaning it – because these days the identity angle is frequently used to dismiss any solidarity with people whose voting habits we detest. But I’m not talking as a member of the “dominant majority” who has never experienced racism, I’m talking as a member of a group that has been relentlessly vilified by the system.

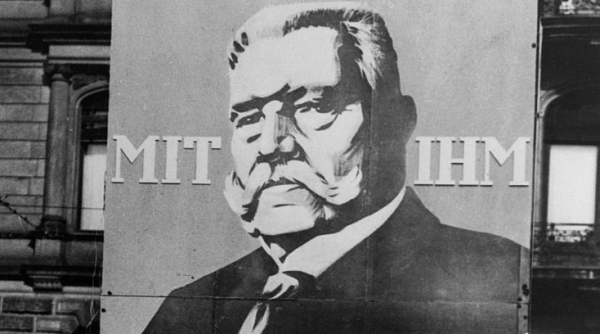

And that vilification is part of the reason. Where did those people who hate me so much get these ideas? Were they just born that way, genetically reactionary? Did they choose these ideas after long and careful consideration, so that we can say they truly represent their innermost beliefs? No, of course not. They are just bombarded with these ideas 24/7. Every tabloid is overflowing with that stuff. But where the tabloids are overt in their racism and perhaps easy to dismiss, others are much more subtle. On TV and in the fancier newspapers they might use the term “mit Migrationshintergrund” (with a background relating to migration), but it’s still a codeword for “filthy foreigners!” Government announcements deplore racism in one sentence while appealing to it in the next.

Perhaps more importantly, completely aside from tone, the “facts” that are presented, the reality that is constructed by both media and government, would logically lead you to believe horrible things about other people. The lies are so shameless and so pervasive that questioning makes you seem like a conspiracy theorist. During the EU-Greece negotiations, German politicians would come on TV and announce things that were literally the exact opposite of what had just happened. Angela Merkel and Wolfgang Schäuble have held long, condescending speeches about the Greek people describing a situation that is 100% false, contradicted by every single statistic produced by independent agencies. They lie right to people’s faces, and they do it so much that it seems like it must be the truth, because no-one would be so crazy as to repeat such nonsense over and over while millions of people are listening.

(Does that sound familiar? And yet these are the exact sort of serious technocrats that everyone wants to hand power to in order to avoid Brexit, and who we are told would have been so much better than Trump, because they know how to run the system. The only thing they know how to do better than Trump is sound coherent while lying.)

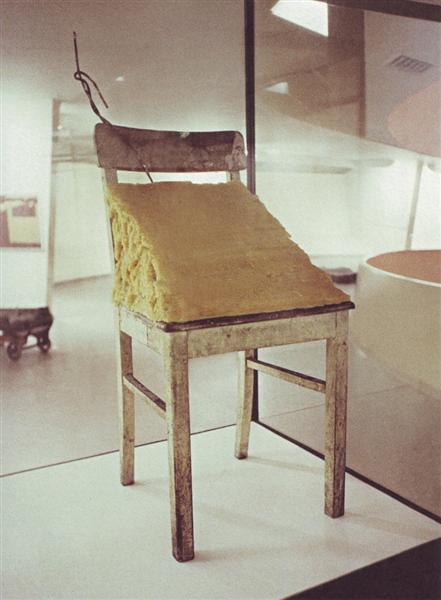

Now think of these working-class people – people who, I must remind you, personally hate me for being Greek – and consider how many chances they’ve had to be exposed to something else. Their education is minimal, their political education even less so. They certainly don’t teach anything politically useful in school, and some of them haven’t even finished school. They know how to use Facebook, but aren’t that familiar with the internet. The places where you are supposed to get “serious” information all spout versions of the same ideology. Meanwhile, their lives are constantly getting worse. Austerity in Germany is not what it is in Greece, but it’s nevertheless real. They struggle to get jobs, and when they do get them, they are terrible. They are constantly unsafe. They have little access to culture or anything uplifting. And the system is brilliantly calculated so that they stay just there, always surviving, never thriving, always available as a cheap workforce.

Sitting in a room with these people, hearing them talk about foreigners (like myself, unless I’m lucky; then I’m the exception, “not like the others”) is pretty disgusting. I have a temper when it comes to these things, so it’s a bit of a miracle I haven’t screamed at anyone.

But that’s a personal, emotional response. Those are all well and good, but they’re not the same as political analysis. Confusing the two is the basis of identity politics, and that’s part of why things have gone to shit as they have. The personal is not the political.

You may be familiar with a famous phrase from the last paragraph of the Communist Manifesto: “The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.” Look at that phrase carefully. Nothing to lose. The basis of socialist thought isn’t that the working class is socially and spiritually better. The goal isn’t to uplift the people who somehow magically deserve it more than others, because they are more advanced, more progressive, more hip. The proletarians have nothing to lose because they have nothing. To be more precise: the foundation of socialist thought is the systemic relationship between workers and capital, in which workers are exploited to produce profit, resulting in their economic, cultural and spiritual immiseration.

Reactionary ideologies are the result of immiseration. They are the result of the atomization of society, of life lived under pressure and in competition. They are also a tool, a method employed by the system to preserve itself. The hate towards Greek people promoted by the German government doesn’t have social or cultural roots; it is a way of dividing the international working class, a way of preventing German and Greek workers from understanding that they are both being exploited, that both their governments represent the same economic interests. It’s not necessary for a politician to hate a group of people to promote hatred against them. It only needs to be politically useful. And when it is politically useful, either those politicians will go with it, or politicians with more useful beliefs will take over their positions. I’m not describing a conspiracy here; it’s just how the system works. In many ways, it’s impersonal.

Despite what we are taught in schools, being determines consciousness: material conditions, not personal philosophies, determine the rise and fall of ideologies. The goal of socialism is to break that cycle, to assert human control over the economy, rather than the other way around. But for that we need the working class.

Why? For one thing, because the working class comprises the large majority of people. In many ways, it is the people – it is humanity. For another, because of what makes it the working class: the term does not denote a cultural group, but an economic relationship to the means of production. That is significant in two ways. One is that the majority of people have common economic interests, from which a huge coalition can be built, which in turn has profound social and cultural implications. The other is that the working class represents the beating heart of the system. Capitalism cannot operate without the working class. We’re frequently told that this is no longer true, because a handful of programmers and designers and artists are making a lot of money, or because of the stock exchange, or even more laughably, because robots will be doing all our jobs by next year. But the truth is that the vast majority of work, the work that actually keeps civilization going, is done by people. And if those people banded together, having understood the nature of their exploitation, they could change everything.

None of this implies compromise with reactionary political movements. As both liberals and traditional conservatives are supporters of capitalism, there is a politically logical tendency for some people from both camps to normalize various far-right movements once those have gained enough power. In Greece there was an attempt to make Golden Dawn (a neonazi criminal organization responsible for multiple deaths) seem respectable; in Germany many will point out that Alternative für Deutschland (a thinly-disguised fascist party) “does have some valid points” about migration; in the US, many will say that “he is our President after all”; in the UK… actually, the UK is such a mess that it deserves a separate article. In any case, the point is that there are those who are willing to adopt the reactionary ideologies that the system requires to preserve itself in order to gain more power inside that system.

Such people should be opposed without mercy. As should those who, despite their class, become so deeply dedicated to destructive ideologies that they become enemies of the people. That’s tragic, but such people exist, and they will have to be defeated. A better world will have to be created for them in spite of them.

However, to actually win against these people will require far more than just the most socially progressive individuals expressing their collective contempt for the misled downtrodden. It will require an analysis of why people are misled, and that analysis must include not just ideology, but economics. And then, on the basis of understanding how material conditions affect the totality of human experience, as many people as possible must be shown where their common interests lie.

The majority of working-class people are not actually reactionary; statistics show that over and over, and the Bernie Sanders campaign recently showed it again. Sanders is not a socialist, and the Democratic Party will never represent anything except the ruling class, but the enthusiastic reaction in poor regions to a Jewish self-proclaimed socialist says a lot. But there is a part of the working class that has fallen prey to deeply reactionary beliefs. I am not asking you to like them. I don’t like them myself. They are not my friends. But they are my comrades – or they could be.

If you want to win, you need people, even people you don’t like. If you want to get those people on your side, you need to fight for them, even if you don’t want to sit at the same table with them. History shows that if you fight for them, they’ll realize you’re not the enemy, and they’ll fight for the common cause with the determination of people who have nothing to lose. It also shows what happens when you look down at them and dismiss them.

Solidarity does not require friendship, but change does require solidarity.